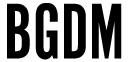

Seeing my mother on camera…it reminds me why it is indeed a film and not any other medium — I want the world to witness first-hand how incredible she is.

1. WHAT MADE YOU DECIDE TO PICK UP THE CAMERA AND START FILMING?

I’ve known for many years — as long as I can remember — that my family’s story needed to be told. Since I began my artistic practice in 2013, I’ve imagined many different forms this story could take: a series of paintings, a book, a play. I’ve felt my mother’s pain for my whole life, and I wanted to give us both a chance to work through it. Making The Taste of Mango felt like the only way I knew how. Seeing my mother on camera, how she speaks so candidly and honestly, and how visible her strength and passion is brings me joy every time I watch the film. It reminds me why it is indeed a film and not any other medium — I want the world to witness first-hand how incredible she is.

Prior to this film, I had only made experimental works for exhibition. I felt that the industry was telling me I needed to make a short doc before I could make a feature, to have a point of reference to show funders I was capable. And so, although I knew deep down that this story was not going to be able to be contained in a short runtime, I gave in to the pressure and began making what I believed was going to be a short about reconnecting with my grandma.

At that time, I thought you needed to have great equipment and fancy cameras to make a film. So I went with a friend and her fancy camera to Sri Lanka, and after spending 10 days shooting there with a small grant from One World Media, Stella Heath Keir (one of the editors) and I tried to make the short. But it just wasn’t coming together. We discussed for a while, and decided that I needed to keep filming with whatever means I had available to me — no funding and just my little Sony HD Handycam — and make it a feature-length doc.

2. HAVE YOU EVER MADE A PERSONAL FILM BEFORE?

In the last three or four years, I’ve been almost exclusively working on things that are about excavating my own experiences, particularly things that have been difficult to comprehend.

I made a short two-channel video piece called Mama in 2018, during my bachelor’s at Central St. Martin’s in London. When my mum was 15 or 16, she started hearing rumours in the family that she had an older sister who she didn’t know about, who had been kidnapped. It took her a number of years, but she managed to track her sister down: she was living in a different part of Sri Lanka. After realising they had never spoken about this, even though they’re very close now as adults, I asked whether I could record their conversation of them speaking about it for the first time. I turned the recording of that conversation into a script, and my sister and I spent a day performing as them, reenacting the conversation. The film cuts between the performed conversation and our real conversations.

And there’s a video piece that I showed at the Whitechapel Gallery in the summer of 2022, called And then it got a bit weird. A few years ago, my drink got spiked. I don’t have any memory of that night, but I have a voice note that I sent to a friend a couple of days later as I was realising what had happened to me. I turned that voice note into a monologue and worked with actors over zoom to perform it. The installation is a three-channel video with one actor’s performance in three different ways. It plays with the idea of the malleability of memory, specifically traumatic memory, and physically replicates a cacophony of voices one might hear in one’s head during moments of crises.

So, long story short, I have only made personal work before, but never with a form intended for cinema until The Taste of Mango.

3. HOW DID YOU PREPARE YOURSELF — AND THE PEOPLE YOU WERE FILMING WITH — MENTALLY AND EMOTIONALLY?

To be completely honest, I didn’t feel the need to prepare myself. I was quite naive in how I approached the film from my own personal standpoint, and didn’t imagine that it would become what it has. As the process continued and evolved, I realised I needed a solid team surrounding me, so that I wasn’t carrying all the decisions on my own. I also took up therapy for a few months during the edit, and started again recently now that the film is being shown to audiences.

My grandmother spoke openly about her life story and was excited to make a film with me. She had specific concerns about what she wanted to exclude from the film, which I was happy to honour. So she had clear boundaries, but from the beginning she was supportive.

My mum has wanted to tell this story for a long time, and so she jumped at the opportunity to make a film about it with me. As I didn’t know exactly where the film’s story was going, I just had to be open and communicative with her at all the stages of the process. I showed her cuts and we discussed how we wanted things to move forward at every pivotal moment. She’s incredibly excited to share the film with people. She had such a wonderful time at the True/False premiere and I know we’ll continue to share more moments like this over the next year of festivals.

4. DID YOU FEEL A “RESPONSIBILITY” TO PORTRAY YOURSELF OR YOUR FAMILY IN A CERTAIN WAY? HOW DID YOU DEAL WITH THAT?

Yes, but it was all a balance. I went through various cuts of the film — some were much more forgiving, and some were much angrier and showed uglier sides of all three of us. I needed to go through that process — especially to have the angry cut and then take a step back and realise that I didn’t need audiences to know absolutely everything in order for them to understand the complexities of each of our characters and stories. In the end, I feel that the decisions I made to arrive at the final cut were made through a combination of knowing what kind of film I wanted to make, and thinking about how the audience might perceive my family. After all, this is something that is going to live forever, and although some things might have been more dramatic or entertaining for audiences, that’s not worth a lifetime of discomfort for my family.

5. WHAT WAS THE MOST CHALLENGING PART OF CREATING THIS FILM?

There were so many challenging moments! I’ll tell you about three of them.

Firstly, fundraising. Other than two very small initial grants at the beginning, I got rejected from every single funding source that I applied for until one year ago, when I already had a rough cut. The amount of work that goes into funding applications is enormous, especially when it’s a personal film and I felt as though I had to be even more vulnerable on paper than in the film itself. When the rejections came through over and over again, it was devastating.

Secondly, the month leading up to picturelock. When I had got to a place in the edit where I thought the structure made sense, the last month of figuring out the final tweaks was agonising. I was so deep in the film that I could barely make sense of it, I was relying on external feedback and at one point I totally broke down thinking that I had ruined the film. I had to take a break, and it was in that break that I unlocked something that now feels central to the story.

And lastly, something that happened at the world premiere at True/False. As I was watching the film with my team and my mum and the audience, I felt an enormous sense of dread. I couldn’t understand that we were watching my film. I thought the film was awful and didn’t know why I was putting people through watching this piece of shit! Then I went up for the Q&A and felt like someone else had inhabited my body and was speaking very eloquently, but it wasn’t me and it wasn’t my film. People came up to me after the film, telling me how much they loved it, and I couldn't believe them, even though I knew I had been so proud of the film when we finished. Thankfully that feeling only lasted until the next morning. The first review came out and it was beautiful, and then more people were coming up to my mum and me on the street, thanking us and telling us how much they loved it, and something clicked back into place. I then spoke to a few other filmmakers and it seems as though it’s actually quite a common experience, but I had never heard of it happening before.

6. WAS THERE ANYTHING YOU HAD TO WORK THROUGH PERSONALLY IN ORDER TO MAKE THIS FILM?

Oh yes…I don’t want to speak too much about this as it’s central to the film, so perhaps I’d just recommend watching it to find out.

7. WHAT WAS IT LIKE IN POST-PRODUCTION, MAKING DECISIONS AND WATCHING IT ALL BACK?

I found it easier to think of “film Chloe” as separate from myself. The film took about five years to make, and four of those years I was shooting and editing simultaneously. I worked with two wonderful editors, Stella Heath Keir and Isidore Bethel, during different moments of the edit process, but I was the main editor and so having that distance between myself and the character on screen felt necessary to reduce feelings of self-consciousness.

Regular feedback screenings with friends, colleagues, and other filmmakers were also crucial to the process. Our producing team has been extraordinary — Producer Elliott Whitton as well as the Executive Producers: Diane Quon, Kellen Quinn, Martha Gregory, Hannah Bush Bailey. They all shared extensive creative notes throughout the process, and I couldn’t have done it without them.

8. WHAT IMPACT DID THIS HAVE ON YOU AND YOUR FAMILY ONCE IT WAS RELEASED OR SHOWN PUBLICLY?

We still haven’t really released the film, it’s been to a couple of festivals so far, so I can’t speak to the impact yet. What I can discuss is how they felt in the lead up, and when I showed them the film.

I decided to wait until the film was at a solid rough cut before showing my mum. I knew that she hadn’t seen a rough cut before, and it might be difficult for her to imagine the work that was still needed to do. I ended up screening it to her three times before the fine cut, and each time she loved it more and more.

Close to the end of editing, my mum decided she wanted to show her big group of Sri Lankan girlfriends — who I call my aunties — and their daughters in London. We rented a screening room, bought a few bottles of prosecco, and watched the film. It was incredible. After we all dried our eyes at the end, we went to the pub and spoke for hours about everyone’s personal experiences that had been brought up by the film. I’ve known these women my whole life and had never heard them talking in this open way. The Sri Lankan aunties’ approval was always going to be the most important, and so after that screening I knew I was ready to share the film.

In the last few months of post-production, my Nana’s physical and mental health was rapidly deteriorating. I went to Sri Lanka to visit her twice before the premiere, and on the second trip, I felt sure that she wasn’t going to be around much longer. I had always planned to show her the full film and to get her approval before showing it to the public, but it just didn’t feel appropriate to put her through any kind of emotional distress during her final months. In the end, I decided to show her parts of the film, skipping forward through any moments that might have been difficult for her, and I explained to her what I was doing and why she might not want to watch them right now. She agreed, and was happy to see anything at all. When it was done, she said she was amazed at how natural we all were on camera, and that she hopes the film will help many people.

Nana passed away two days before the New York premiere at First Look. I shared the news with the audience during the Q&A and the whole event ended up feeling like a wonderful memorial for her. What’s strange is that for both me and my mum, it’s hard for us to grasp that she’s gone, because she’s so alive through this film.

9. WHAT’S ONE THING YOU WANT TO SHARE WITH PEOPLE MAKING PERSONAL DOCUMENTARY FILMS?

Be patient. It might feel excruciating that it’s taking so long, you might feel like you just want to get it done, but it will take the time it needs. You’ll know when it’s done when it no longer feels like it belongs to you anymore.