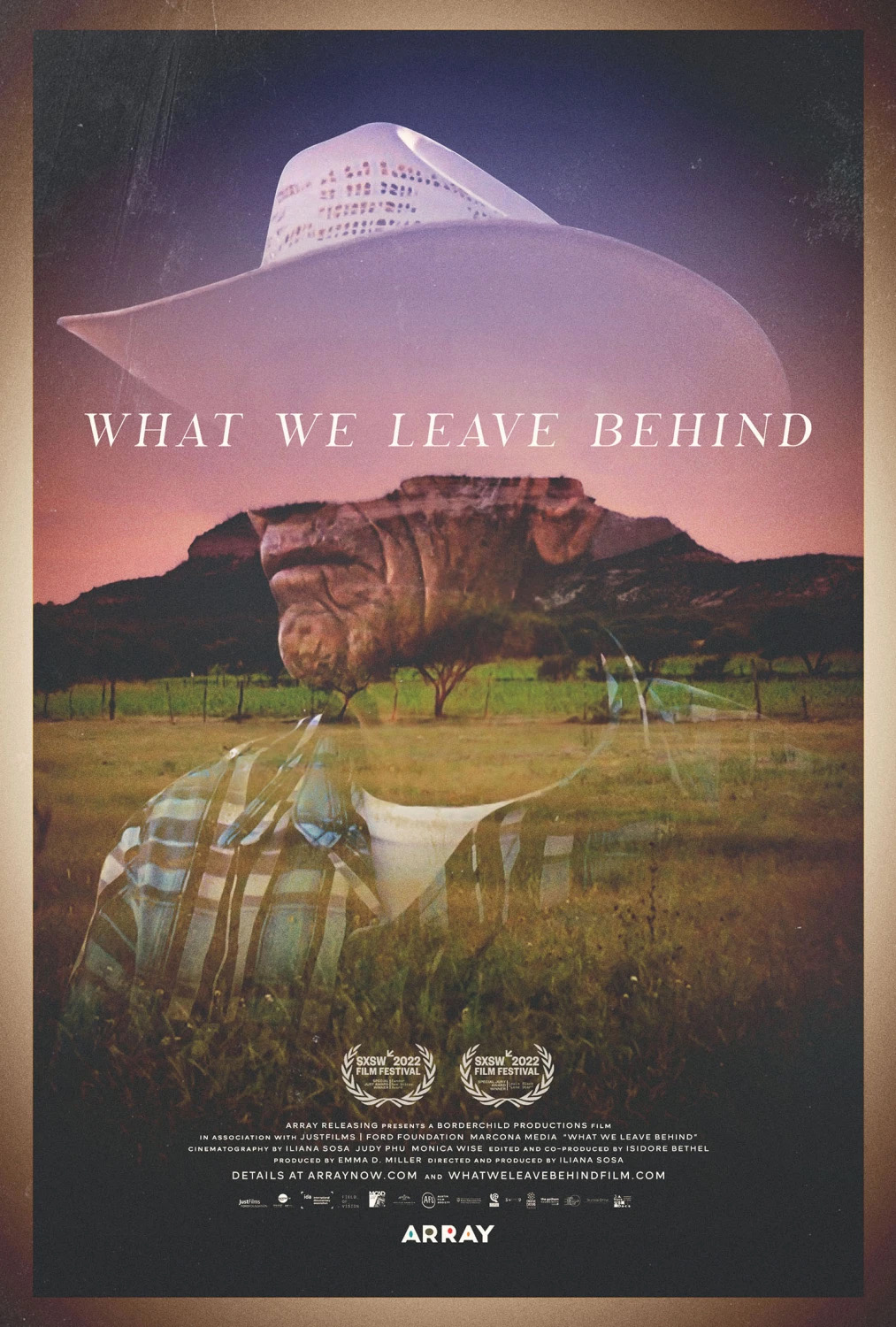

As a first-generation child of Mexican immigrants, I never thought that the story of my grandfather would resonate in this way with so many communities outside of my own. - Iliana Sosa, Director

The U.S.-Mexico border has been part of Sosa’s family history for at least three generations, but the politics of how it’s impacted them can’t be reduced to stereotypes and sound bites. At one point, Sosa asks her father about his years as a bracero, one of many Mexican farm hands who were granted entry into the U.S. to meet labor shortages in the mid-1950s. The specificity of Moreno’s memories as he offers his lived experiences serves to center his humanity and resilience.

Since the film’s success across numerous film festivals, What We Leave Behind has been picked up by Ava DuVernay’s production company, ARRAY, and debuted commercially on Netflix on September 30th. Sosa called in from her home state Texas as we discussed the film’s wide-reaching audience and impact.

Jireh: We hear your voice as a throughline throughout this film. It’s almost like we’re watching from your perspective. Was this an intentional choice that you made while you were interviewing your grandfather and trying to get different shots?

Iliana: Honestly, this is my first feature documentary. I had made other short documentaries before, but I was learning the craft and process of making documentaries as I was making this film. It was intuitive in the sense that I never felt like I wanted to be on camera.

I always felt this is my grandfather's story - my family's story - of how we've managed to build a home despite borders, but more importantly, across generations. Once we showed the film at a rough cut stage, people were saying the same thing: “We want to see more of you.” You hear me, but you don't see me. I felt like I discovered my voice even more in the voiceover sections.

I felt my grandfather and my family had been quite open and vulnerable with me. I thought, “Well, I should do the same in some way.” I already felt vulnerable making the film but I think those voiceover sections give you a little bit more insight into who I am as a person and a filmmaker.

As you were looking through your footage and working with your editor when did the narrative start to take shape? How did you decide how it should chronologically flow and focus on the overarching themes you wanted to highlight?

My initial idea was to document my grandfather's journeys as a bracero. [With] the bracero program, the U.S. government contracted Mexican farmworkers during World War II because there was a shortage of labor. My grandfather was one of these men and there are not many of them left. I wanted to make sure that I got those stories and listened to him talk about those experiences—but then the film evolved.

This is a film that was seven years in the making. It took a while because I wasn't filming every year, but the story shifted in the last two years. In the last year of my grandfather's life, he said, “I'm building a house.” I thought, “That's super interesting, I should follow that.” It wasn't my intention. I thought I was done filming. But I did go to film, and that became the story. So to be honest, the story shifted so much in the edit and after I shot that footage of him working on that house.

I always knew that I wanted to focus on him, on themes of labor and generational separation. I tried to capture the rhythm and the pace of this town because I have vivid memories as a child of going there and feeling at home and ease. It's just a very different way and pace of life. I knew I wanted to include all that, but I didn't know that the film would evolve into what it is now.

Isidore [Bethel] gave us a brilliant exercise before we started working together. He said, “Send me some of the raw footage that you find inspiring, some that you find frustrating, or footage that elicits certain emotions.” I did that, and eventually we came up with an assembly that included some of our favorite scenes, scenes that moved us or triggered an emotion in us. From there, we slowly started seeing what the story was becoming. With a documentary, you often find the story in the edit, but also the film will tell you what it wants to be and that's what happened with this film.

You were documenting some of the most intimate moments with your family. How did you decide what or what not to film when your family was in these vulnerable moments? How did you explain the process to your family as you were interviewing them?

In production, before my grandfather got sick, he loved the camera and was always very participatory. He was very much a director saying, “Let's go here, let's film here.” But when he got sick, I brought a camera and there was no crew there with me.

I was there, I was living his decline. I was feeling that just as the other people in that room as I was filming him. In the editing room, we thought, “What's the best way to present this and not in an overly romantic way and not exploiting someone who is dying?” We were very cautious of what to show and what not to show.

Particularly the moments when he is being massaged, I remember asking my mom, “Is this okay?” I filmed the rosary scene with my cell phone. At the moment, my family didn't say no. I think they were so used to me having the camera around. There was never any resistance, particularly with that rosary scene.

We wrestled with that rosary scene for a while and then settled on it because I thought, especially given what's happened with the pandemic, so many people have died alone. In Mexican culture and many cultures, it's common to be at someone's bedside as they pass. That's how you celebrate life and death. You're sending them off as a family.

I thought it was important to show that there’s something beautiful in that he didn't die alone. Everyone that could be there was there. I have an aunt who is undocumented and she wasn't able to go to Mexico when he died. My grandfather told her not to come because she wouldn’t be able to come back to the U.S. These are all realities that immigrant families - not only Mexican ones - are grappling with. This is just being human. I was thinking, “How do you make sure that someone that's passing is honored?”

You’ve reached the end of an odyssey of almost 10 years. This film has won numerous awards and was picked up by Ava DuVernay’s company. What do you feel as you reflect on your growth as a filmmaker and look at the culmination of all this hard work?

It's so surreal because I remember early on, I had no money and I was doing it all by myself. Eventually, I was able to fundraise for [the film], but I remember just having all this footage and not knowing what to do and feeling kind of depressed and down. I had all this stuff but I [didn’t] know what to do with it. I kept applying for grants, often getting rejected multiple times. It was a long process to get to where it is now.

I have an amazing team. My producer, Emma D. Miller, and co-producer, editor and co-writer, Isidore Bethel, helped make the film what it is and I'm very grateful for their support. I have to pinch myself right now. I don't think my family thought I would finish because it took so long. Now, they're telling their friends and other families about it.

As a first-generation child of Mexican immigrants, I never thought that the story of my grandfather would resonate in this way with so many communities outside of my own. I truly thought this was just something that was part of our family. That's been the most rewarding part of it. It makes me immensely proud of my family, of our team. Just this morning, I talked to my mother and she said, “This is the inheritance that your grandfather's leaving you.” Our family doesn't come from money, and it's such a beautiful legacy. I see it as a tribute to my elders.

My grandfather never went to the movies. He didn't have the resources or the time, and in his little town, there's no such thing. Now to see his face on these posters and as people across the country are going to see him on screen — it's coming full circle. It's making me aware of the importance of celebrating our history and elders because they’re powerful. And people are yearning for that. I'm just very blessed and full of gratitude.

Your film isn’t overtly political, but I also see it come out in the ways you humanize your family and talk about migration and the natural movement of people across borders. You started filming this before Trump's administration and the anxiety around immigration that heightened during those four years. Were border politics on your mind as you were making this film?

There are a lot of stories about the border and families being divided, but I didn't intend to make a political film. Inherently, documentary filmmaking is political by nature, but I didn't want to make an issue-oriented film. I just wanted to make a portrait of my family, of my grandfather. I see our family as a typical modern-day American family.

Sure, we live by the border and I was born and raised in El Paso, but that's just my everyday life in between worlds. It’s just like my grandfather working here in the U.S. as a bracero and going back to Mexico. He was always traveling and that was just his life. It’s political because of the circumstances of the border, his having to leave seven children behind while he was working in the fields, and my mother raising her siblings. That was life and what they had to do to survive.

I see this as a story of survival, and perseverance, but also the portrait of a man who was very stubborn up until he died. He set out to make this house and in many ways always set out to take care of his family one way or another — it didn't matter how.

As I watched this film, it challenged my ideas of what deserves attention and praise in our films. How do you think this film normalizes narratives that don’t receive mainstream recognition?

I was just talking to another filmmaker at a festival and she said, “Your film inspired me because I've been with my grandmother in Wuhan filming her in all these small but intimate moments and not knowing what to do with that footage. I watched your film and you're just focused on the everyday. This encourages me to go back and do something with it.”

We sometimes minimize our own stories and we shouldn’t, especially as people of color. I think we've been told what a certain story needs to be or look like to even be on camera. As a filmmaker, I think there's beauty in the everyday, and there's also beauty in the faces of people who we're not used to seeing on screen. We need more of that.