The way a film walks into our consciousness communicates a perception of the world, engenders a state of mind to learn and unlearn — it’s all consuming.

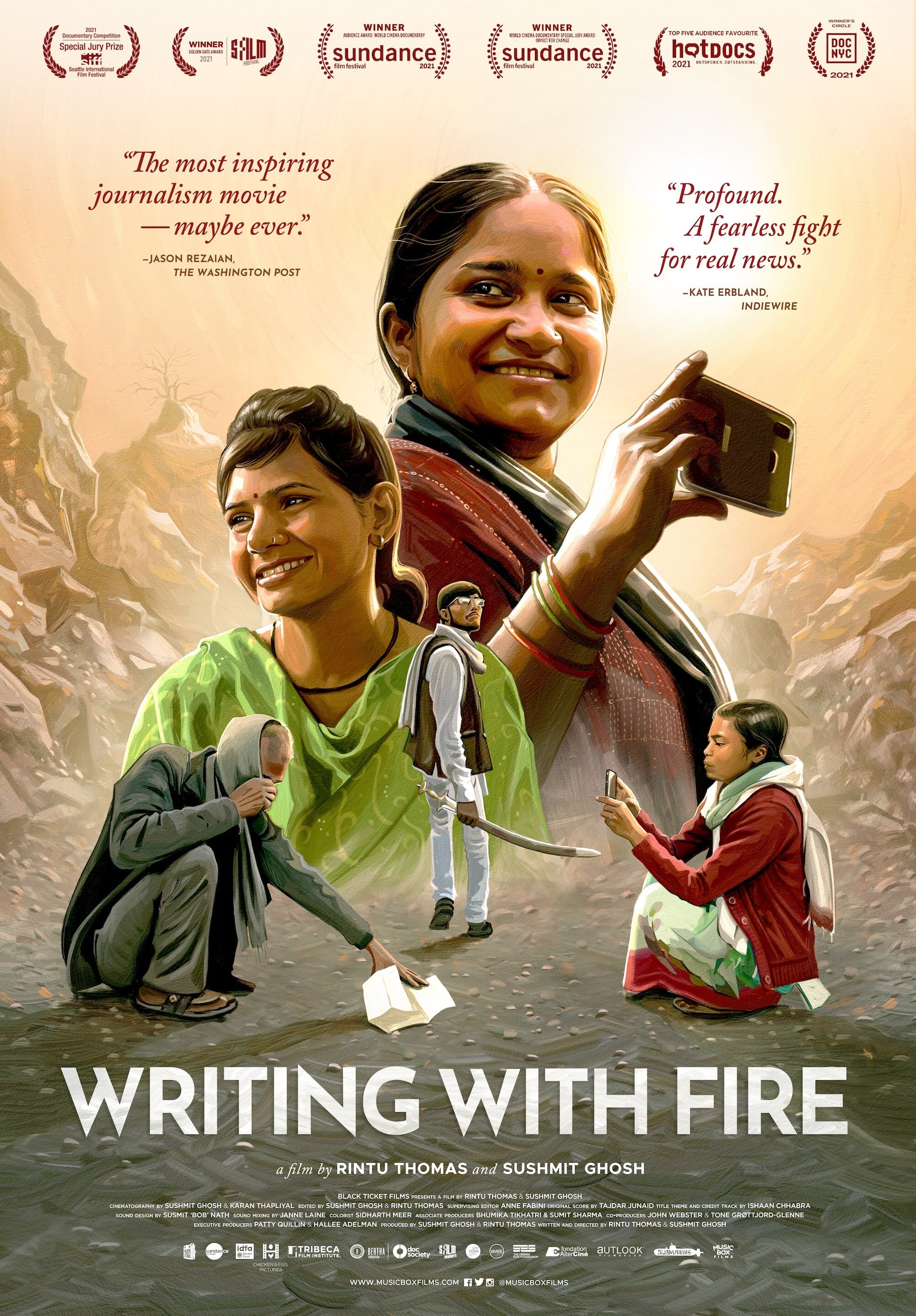

Writing with Fire was nominated for Best Documentary Feature at the 94th Academy Awards, becoming the first Indian film to ever be nominated for an Oscar in this category. But for Thomas, this truly is a reality she would have never imagined herself embodying.

Thomas was raised in a working class family and has spent the majority of her life in Delhi, India. Her parents moved to Delhi in search of social mobility and expected her to follow a “traditional” career path. Ultimately, Thomas was driven by wanderlust and eventually found her way to filmmaking when she pursued her master’s degree at Jamia Millia Islamia University.

Filmmaker and fellow BGDM Mafiosx Alicia Soller had the pleasure of speaking to Thomas about the foundations of her career in documentary filmmaking, Writing with Fire, and pushing the doors open for marginalized filmmakers of color.

Alicia Soller: What draws you to filmmaking as a means to tell stories?

Rintu Thomas: I grew up reading books at home, in libraries, at railway stations — relishing words was my portal to the world. After studying literature for my bachelor’s, I wanted to build a career in writing. Curiously, I found my way into film school where, for the first time, I was writing with images. The way a film walks into our consciousness communicates a perception of the world, engenders a state of mind to learn and unlearn — it’s all consuming.

I think I’m drawn to this power of the medium which is not just aural and visual, but also so emotional. You’re in it with your whole being — crying, scared, laughing, thinking. There’s a plethora of feelings that consume you for those 90 or so odd minutes. And a good film never really ends when the screen goes black, it lives and loves and gnaws within you. I find no other art form to have that kind of singular power of putting you back in touch with yourself.

Why did you gravitate toward the women of Khabar Lahariya and their stories in Writing with Fire?

I've always been interested in the role of women in democracy. And when I'm interested in people, it is their quiet resilience that I’m naturally drawn to. “How does a world imagined by those on the margins of power look like?” has been the central preoccupation of most of my work.

When Sushmit and I saw a photo story about the work of Khabar Lahariya, it spoke to us about women who are creating an alternative structure of power. A newsroom led by semi-literate women from marginalized communities for 14 years, most of whom had never touched a smartphone, was on the cusp of pivoting to digital. Whether they’d succeed in this endeavour or not did not matter to us. The imagination, intellect and tenacity that we experienced in that room felt like the heart of the story we wanted to tell.

While the film from the very start felt highly intersectional. It is as much about gender and caste as much as it is about democracy and media. We wanted its language to be one of intimacy.

You mentioned to me that it took you 5 years to finish Writing with Fire. Did the process of making this film unfold in ways that you expected?

[Sushmit and I] thought it would take two years, mostly because the three protagonists of the film emerged very naturally in the very first meeting we had with the team. That’s quite rare. In the years that followed, the film found its depth when the women opened their homes to us and the camera, introduced their families both to us and the process of filming, allowed us the access to their personal and professional worlds. And such a delicate journey of trust has no roadmap. It took shape [over] four years where each of them had their own personal storylines which coalesced in many ways with their professional worlds as journalists.

To have protagonists who are, themselves, media makers, who understand how access and consent work, who were filming their realities and editing their stories as we filmed ours, led to many informed conversations between all of us, which I believe gives the film its intimate tone, fierce syntax and delicate beauty.

The post-production of this film was as exciting and exhausting in equal measure. We both, apart from being directors, producers, were also its editors, building it piece by piece during the pandemic. The coming together of the story took us through familiar and expected images as well as unexpected connections and meanings. Looking back, I think the one thing [that] didn’t change from the first day of filming ‘til the edit hard drives were taken away from us by the colour graders is the quiet power that we wanted to imbue the film, its world and its protagonists with.

How was the experience of releasing Writing with Fire into the world?

Birthing a film during the pandemic turned out to be an unpredictable scenario for us, with distributors dealing with a glut of films from 2020 that were vying for release. While Writing With Fire had its premiere at Sundance in 2021, where it won two awards — the much loved Audience Award and Special Jury Award Impact for Change — this did not translate into a global distribution deal from a studio or OTT, which surprised us. The challenge was to be able to put the film into the world, while jostling for space with much bigger studio titles.

If a festival invited the film and us for a virtual conversation, we would scoop it up with gratitude. In many festival panels and discussions, our protagonists also joined us. The film began building a momentum of love which multiplied its reach. We focused on a very robust festival run with the film. It played in over 150 festivals and won over 35 awards. [We] qualified the film with a limited theatrical run in the U.S. and continued to ensure that the film was seen by as vast and varied demography — and this became the game-changer for us. The diverse tenor of the documentary branch has had a huge role in Writing With Fire finding a nomination for an Academy Award. We call this the gift of community, people power.

Rintu with the three main protagonists of the film.

Rintu with the three main protagonists of the film.

Can you describe your feelings around being nominated for an Academy Award?

There is a video of us that records the exact moment when the nominations are being announced. We are jumping, losing all decorum and embodying disbelief. Next morning, this video was all over the internet and the whole country had erupted in joy. Our inboxes exploded and so many filmmaker friends and colleagues called in saying how this felt like their own personal victory. As independent non-fiction filmmakers working in an ecosystem of strapped resources and scant opportunities of distribution at home, we felt like we had knocked down a tightly shut door. From watching the red carpet on television to walking it has been surreal in every way. In just a year since then, the conversation in India has evolved from “first Indian documentary nominated” to “which is the next Indian doc that will be nominated and win.”

That said, I’m not an Oscar evangelist, and doing an Academy campaign brought me face to face with so many layers of baked-in systemic inequities that need dismantling. How an independent film with no studio or global distributor found its way into Hollywood’s hallowed belly is testimony to the intentional diversification of the Academy’s documentary branch. We were nominated alongside three other filmmakers of color and that made the whole journey a lot more meaningful for me.

But there is a lot of work that needs to be done, especially around the scant knowledge about how to run a campaign — a word that itself needs some serious interrogation. Our strategy was driven by the deep desire to expand the reach of the film, by putting collective experience and wisdom to use. We had learned everything about how this machinery works and there's not a single email that I wrote to fellow indie filmmakers that was not answered. And I never take that for granted. I feel like it’s my job now to pass it on.

What are some lessons learned from the totality of your experience with Writing with Fire that you want to carry on to your next projects?

There have been many learnings [in putting] together this film, whose journey mapped half a decade of my life. And one aspect that I feel is important to share as a learning with the field is the importance of managing expectations, especially when a film becomes bigger than what both filmmakers and participants can ever imagine it to be. And how complex and risky this journey can be for those of us who live and work in fractured democracies.

The participants and organization profiled in Writing With Fire not only celebrated the film and their portrayal, they travelled with us for over a year on a mutually created distribution strategy. However, after the nomination was announced and the far right political party came back to power in the region they work in, — the double timing of this could not have been more ironic — they suddenly changed their relationship with the film.

Most of us as independent documentary filmmakers follow processes of storytelling that are intimate, thoughtful and deliberate. However, the world of awards campaigning, with its perception of fame and media frenzy, brings a whole different scale of attention to a film, its makers and its participants. And the collision of these two worlds can be chaotic. I would create the time and space it needs to prepare myself and the people in my film by sharing what this kind of amplification means and what it does not mean — for all of us. For me, making a film is a very deep, long and sustained process and it’s quite painful when forces larger than us start unravelling the threads of these relationships of trust.

In the last year, I’ve had several conversations with filmmakers and realised that this is one aspect of a film’s journey that a lot of us have experienced but we feel reticent to talk about because it feels like a personal failure. With some distance from the painful experience it was for me, I feel like this is a very important conversation that needs to be centered as we are making our films and imagining new journeys for them.

What advice can you give to women of color who are new and emerging filmmakers?

When I was starting out in my career, I didn’t know anything about running a business. And I’ve learnt a great deal by asking, negotiating, disagreeing, failing and unlearning. So, don’t be afraid to be seen and heard asking questions.

Earlier, I’d tend to hold back, with a biased evaluation of self-image. But once I started reaching out, I’ve had the most practical, warmest and the most compassionate advice from fellow filmmakers, and there's so much power in that because you realize you're not alone in this. It's amazing how much people are willing to share if we just reach out.

And finally, everything is negotiable. Lead with open conversations in situations that feel unjust and you'd be amazed by how much can be achieved by staying in the game, negotiating rather than accepting things as they are or walking away.